This is the first in a series of four pieces that were originally featured as guest blogs on http://www.primarytimery.com by Clare Sealy, who I would like to thank for her support with their writing and sharing. I would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the teaching staff at St. Matthias School in Bethnal Green, Andrew Percival (@primarypercival) and the staff at Stanley Road Primary in Oldham, Jon Hutchinson (@jon_hutchinson) at Reach Academy Feltham, and Mark Enser (@EnserMark).

Earlier this year, I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to review my school’s geography and history curriculum, and finalise our schemes of work. As part of this process I did a lot of research on the subject content, and greatly improved my subject knowledge, particularly in geography. While doing so, I’ve thought a lot about what the ideal curriculum would look like – what would be the best way of systematically developing children’s knowledge and skills so that they master the KS2 objectives by the time they leave in Year 6? I’ve written some of my thoughts into these subject guides in the hope that they may help other teachers who are in the process of reviewing their curriculum.

The guides are written on the understanding that your school is teaching the English National Curriculum 2014, and is mainly concerned with how to select content that will ensure you cover the National Curriculum content across each key stage, as well as suggestions as to how the objectives can be grouped and sequenced in order to create a coherent, logically sequenced curriculum. What are you teaching, when, and why?

As the objectives in the Key Stage 1 geography curriculum are mainly fixed and explicit about what children should know and be able to do, the choices that need to be made are mainly regarding the order in which the objectives will be taught, how far they should be broken down into smaller steps, and how many times they should be revisited across the key stage in order to ensure that children remember what they have been taught. (One of the criteria relating to Impact under Quality of Education in the 2019 Education Inspection Framework is that “over the course of study, teaching is designed to help learners to remember in the long term the content they have been taught and to integrate new knowledge into larger concepts.”)

However, there is one objective which requires decisions to be made before you can create a definitive list of the geography that you will be teaching in Key Stage 1:

- understand geographical similarities and differences through studying the human and physical geography of a small area of the United Kingdom, and of a small area in a contrasting non-European country

First, what will your small area of the UK be? It would seem to make sense to combine this study with the following objective:

- use simple fieldwork and observational skills to study the geography of their school and its grounds and the key human and physical features of its surrounding environment

In that case, the small area of the UK would be the local area of your school.

Alternatively, you could separate these two objectives, choosing a contrasting area of the UK to study in addition to the surrounding environment of your school. This would be particularly important if your pupils have limited experience of different environments – if your school is in a city, studying a rural or coastal area would be an important addition to your children’s cultural capital.

Secondly, which contrasting non-European country will you choose? There are several possible bases for making this decision:

- A location that reflects the background of a significant proportion of the school population or a significant ethnic minority group in the local area. For example, if your school is an inner-city one with a high percentage of Bangladeshi Muslim pupils, studying an agricultural region of Bangladesh could be a good choice.

- A location that adds to the pupils’ understanding and appreciation of diversity by providing cultural as well as locational contrast.

- A location in a continent that does not feature in Key Stage 2, so choosing it for study in Key Stage 1 will ensure that your pupils have sufficient understanding of a range of countries around the world. I would suggest waiting until you have decided on which locations in Europe and North or South America you will teach in Key Stage 2, as well as the history units you will be teaching. Plot these locations on a world map – is there a continent or country that is not represented, but which you feel it is important for the children in your setting to have experience of?

- A location that links to an area of study in a different subject – a history topic or a text that is being used in English. Just be careful that if you make the decision for this reason, the location you select has sufficient learning potential (you’re not sacrificing the geography for the sake of the link).

Whichever reasoning you base your decision on, make sure that you choose an area which includes the physical and human features that are studied in this key stage, since the original objective specifies comparing physical and human geography.

Physical features: beach, cliff, coast, forest, hill, mountain, sea, ocean, river, soil, valley, vegetation, season and weather

Human features: city, town, village, factory, farm, house, office, port, harbour and shop

Now you know what needs to be taught, how will you organise this into units of work? What is a logical way in which to sequence these units?

- identify seasonal and daily weather patterns in the United Kingdom and the location of hot and cold areas of the world in relation to the Equator and the North and South Poles

The first part of this objective (seasonal weather patterns), links to the Year 1 science objectives on seasonal change, which include the requirement to observe and describe weather associated with the seasons, so it would make sense to teach them together. Consider organising this into four short blocks across the year – one for each season at the appropriate time of year – so that children can experience what they are learning about first hand. Remember that there’s a second half to this objective which will need to be slotted in later.

When sequencing the remaining objectives, it would seem to make sense to start with those focused on the UK in Year 1, and gradually widen out to cover the more abstract world locational knowledge in Year 2 (although this sequence is not essential). The following is a suggestion as to how to split the objectives between Year 1 and Year 2:

Year 1 (in no particular order)

- understand geographical similarities and differences through studying the human and physical geography of a small area of the United Kingdom

- name and locate the four countries and capital cities of the United Kingdom and its surrounding seas

- use world maps, atlases and globes to identify the United Kingdom and its countries

- Identify characteristics of the four countries and capital cities of the United Kingdom

Year 2 (in no particular order)

- understand geographical similarities and differences through studying the human and physical geography of a small area in a contrasting non-European country

- name and locate the world’s seven continents and five oceans, as well as the countries, continents and oceans studied at this key stage

- identify the location of hot and cold areas of the world in relation to the Equator and the North and South Poles

Of course there are many ways of grouping the objectives into units, which will depend on the location of your school, the backgrounds of your pupils and the history units you choose to teach. Also, keeping in mind the need for children to regularly revisit and have opportunities for retrieval practice, it will be important to continue to reference and build on knowledge initially taught in Year 1, throughout Year 2. You may also decide to introduce children to the seven continents and five oceans in Year 1, or to split the study of the school and its grounds into two units, with more in depth fieldwork taking place in Year 2 when children have developed a better understanding of measurement and statistics.

Geographical skills and fieldwork

Geographical skills and fieldwork should be included in each unit, with the level of challenge gradually increasing throughout the key stage. As with the locational knowledge objectives, it is vital that prior learning is regularly revisited and built on, so there should be several opportunities throughout both Year 1 and Year 2 for children to practice using compass points to describe locations on maps for example.

When introducing new human and physical features, and new locations, following this routine would be a good way of ensuring that children’s map skills are developed well:

- Identify in photographs

- Visit in real life if possible

- Identify in aerial photographs

- Identify on a map (OS map symbols)

- Locate on a map of the UK or the world

- Describe its location in relation to other places or features studied

- Locate in an atlas

This sequence could be gradually developed throughout the key stage, so that by the end of Year 2 children are able to do all of the above confidently.

The unit on seasonal weather patterns provides a good opportunity for developing fieldwork skills by recording temperatures and measuring rainfall. Additionally, the unit of study of the school grounds and the surrounding environment should mainly consist of fieldwork. If you have chosen to study a contrasting area of the UK as well as the school’s local area, additional fieldwork could be carried out on a visit.

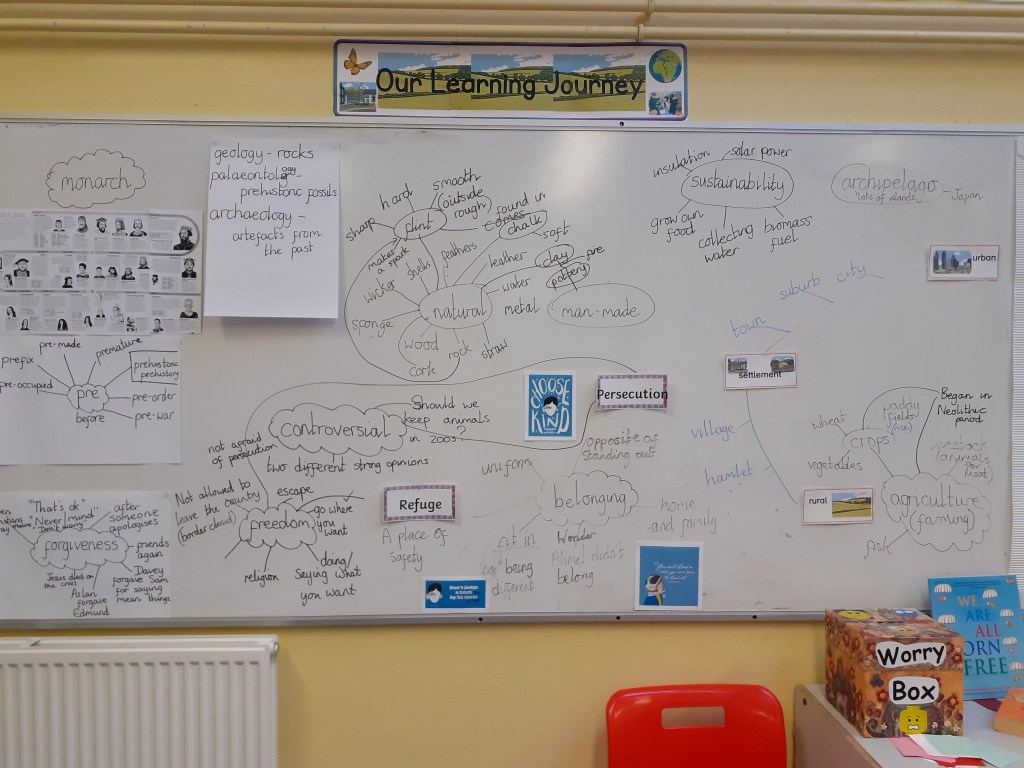

Opportunities for retrieval practice

Including an ‘orientation lesson’, which looks at the location of places that are important, using the list of activities above to explore it fully, at the start of each history unit, could be a useful way of providing children with opportunities to revise previous locational knowledge, use their geographical skills, and introduce them to a wider variety of countries.

Additionally, looking carefully at the texts you have chosen to teach from a geographical perspective could provide some useful opportunities. This may be using ‘orientation lessons’ as described above, or it may be identifying human and physical features in illustrations or using knowledge to create a clear picture of a setting. It’s worth noting that while vegetation is on the list of physical features, if plants or trees have been planted by people, such as flowerbeds in a park, they are in fact human features. Illustrations or mentions of different features in stories could help to provide children with plenty of examples (and non-examples) so that they develop a really secure understanding.